Add Actions to Your State Machines

In the previous article, we looked at how to transition a set of boolean flags into a simple state machine. Here we’ll take it a step further with a different example, and make our states and transitions do actually useful things.

Actions on the Side 🔗

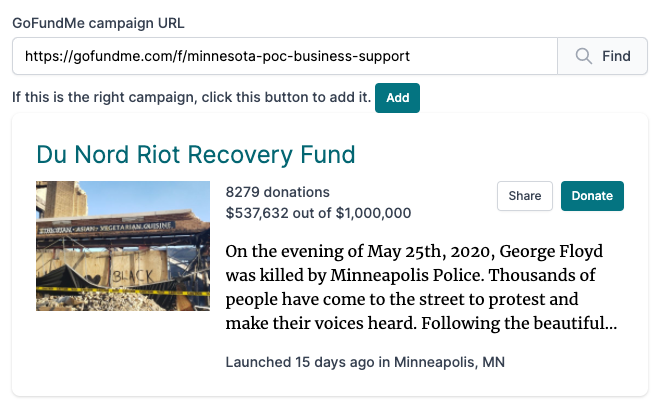

FundTheRebuild.com is a website designed to highlight GoFundMe campaigns that haven’t gone viral and need a bit of extra attention. The “Add a Cause” page allows people to submit their own campaigns.

When opening the page, users see a text box where they can paste the URL of a GoFundMe campaign. Upon submitting the form, the page tries to find a valid campaign. It displays the details to the user, who can then click an “Add” button to put the campaign in a queue to be approved and added to the site.

The initial implementation of the Add page uses a basic state machine with seven states:

{

initial: IDLE,

states: {

[IDLE]: { // We start here

'search': SEARCHING

},

[SEARCHING]: { // Looking for the campaign the user selected

'search-succeeded': SEARCH_FOUND,

'search-failed': SEARCH_ERROR,

},

[SEARCH_ERROR]: { // Couldn't find the campaign

'search': SEARCHING,

},

[SEARCH_FOUND]: { // Found the campaign!

'search': SEARCHING,

'submit': SUBMITTING,

},

[SUBMITTING]: { // Adding the campaign to the database

'submit-succeeded': SUBMIT_SUCCEEDED,

'submit-failed': SUBMIT_ERROR,

},

[SUBMIT_SUCCEEDED]: { // It worked!

'search': SEARCHING,

},

[SUBMIT_ERROR]: { // It didn't work.

'search': SEARCHING,

}

}

}

The state machine starts in the IDLE state, proceeds through the SEARCHING states, and then moves to SUBMITTING if the user confirms that they want to add the campaign. At most points in the process, clicking the Search button wll go back to the SEARCHING states again.

While the state machine simplifies the logic of figuring out what to display on the screen, most applications need to do more than just show things on the screen. Currently these other actions exist alongside the state machine, and interact with it but are not part of it.

async function submitCampaign() {

stepState('submit')

try {

await client.post('/api/submit-campaign', { json: campaign });

stepState('submit-succeeded');

} catch(e) {

stepState('submit-failed');

}

}

async function findCampaign(url) {

stepState('search');

try {

currentCampaign = await client.get('/api/get-campaign',

{ searchParams: { campaign: url } }).json();

stepState('search-succeeded');

} catch(e) {

stepState('search-failed');

}

}

This mostly works fine, but it has issues. In the previous article, we established a model where we could send any event to the state machine at any time, and it would use the transition definitions to go to the correct next state (or ignore the event). But here, future alterations to the code must use these functions instead of just sending events to the state machine. Otherwise the network requests won’t actually happen.

Worse, the functions send the network requests without any regard for if the state machine actually responded to the event. We could add extra code to fix that, but it duplicates the logic already in the state machine – another source for bugs.

Integrating Actions 🔗

The more we can do by only talking to the state machine, the better, but we obviously can’t give up the ability to actually do stuff. So we’ll put actions and their corresponding state transitions into the state machine itself.

There are various places and ways that actions can happen. We’ll add four types:

- Synchronous actions during a specific transition

- Synchronous actions when entering a state

- Synchronous actions when exiting a state

- Asynchronous actions that happen as part of a state

Synchronous actions are any “plain” Javascript code that modifies some of the variables related to the state machine (e.g. currentCampaign in the examples above), while asynchronous actions would be anything involving Promises, callbacks, setTimeout, etc.

Here we’ve limited asynchronous actions to running inside states. It’s possible for transitions to trigger asynchronous actions, of course, but that causes some complications, such as leaving the state machine in between states while the transition runs, and having to deal specially with errors. So we’ll only officially support asynchronous actions on states themselves.

A Quick Digression into State Machine Theory 🔗

Traditionally, there are two types of state machines that differ primarily in how their outputs change. A Mealy state machine’s outputs depend both on the current state and the inputs to the state machine. A Moore state machine’s outputs depend only on the the state it’s in, and its inputs are used solely to determine the state.

When drawing state diagrams, the actions of a Moore state machine are on the states, and the actions of a Mealy state machine are on the transitions. For the most part, state machine definitions can be translated between the two models by moving around the actions and possibly adding or removing states.

This distinction really matters most when putting a state machine into hardware, where adding extra configurability comes with a cost. For modern programming languages, a hybrid approach that allows actions both on transitions and states works just fine. The entry and exit actions are equivalent to placing an action on all the transitions going into or out of a state, so this is a lot like a Mealy machine, but it’s more convenient to write and maintain.

Global Event Handlers 🔗

As an aside, one notable thing about the state definition at the top is that most of the states have a 'search': SEARCHING transition. We can alter our state machine model to include global event handlers which will run on any state that doesn’t have its own handler. This further reduces duplicated logic, and leaves us with this:

{

initial: IDLE,

on: {

'search': SEARCHING

},

states: {

[IDLE]: {}, // We start here

[SEARCHING]: { // Looking for the campaign the user selected

'search-succeeded': SEARCH_FOUND,

'search-failed': SEARCH_ERROR,

'search': null,

},

[SEARCH_ERROR]: {}, // Couldn't find the campaign

[SEARCH_FOUND]: { // Found the campaign!

'submit': SUBMITTING,

},

[SUBMITTING]: { // Adding the campaign to the database

'submit-succeeded': SUBMIT_SUCCEEDED,

'submit-failed': SUBMIT_ERROR,

'search': null,

},

[SUBMIT_SUCCEEDED]: {}, // It worked!

[SUBMIT_ERROR]: {} // It didn't work.

}

}

In the SEARCHING and SUBMITTING states we define empty transitions for search to indicate that the global handler should not be used.

Adding Synchronous Actions 🔗

Ok, with those asides out of the way, let’s get to the real task. Synchronous actions are pretty straightforward, so we’ll add those first.

First, we change our event handler from just the name of the target state to an object, which can specify an action, a target state, or both. The event handlers are also moved under the on key to make space for the other actions. I’ve used object keys similar to the XState library to make it easier to move from our homegrown implementation to XState should you want to in the future.

Here’s a partial example just to demonstrate the syntax.

{

// Allow defining global handlers. This `cancel` handler runs for any state that doesn't

// have its own handler.

on: {

'search': {

target: 'SEARCHING',

action: (context, { event, data}) => { ... },

}

},

states: {

SEARCH_FOUND: {

entry: (context, {event, data}) => { ... },

exit: (context, {event, data}) => { ... },

on: {

'submit': {

target: 'SUBMITTING',

action: (context, {event, data}) => { ... }

},

// But we can also define an empty transition to

// NOT use the global handler or do anything else.

'search': {},

}

}

}

So when entering the IDLE state, the state machine runs the entry action, and when leaving it, the machine runs the exit action. When the search event comes in, the machine runs the associated action and then enters the SEARCHING state.

All action functions are passed the name of the event that caused the transition, and any data associated with the event. They also receive a context object, which is shared between all the action handlers and can also be accessed by outside code that works with the state machine. In this case, context would be an object containing the currentCampaign variable used above.

The stepState function is updated to handle actions as well, and we’ll start to make the function reusable too:

import { writable } from 'svelte/store';

function createStateMachine(machineConfig, initialContext) {

let currentState = machineConfig.initial;

let context = initialContext;

let store = writable(null);

// Update the store so that all subscribers will be notified of the change.

function updateStore() {

store.set({ state: currentState, context });

}

function sendEvent(event, data) {

let stateInfo = machineConfig.states[currentState];

let next = (stateInfo.on || {})[event];

if(!next) {

// No transition for this event in the current state. Check the global handlers.

next = machineConfig.on[event];

}

if(!next) {

// No global handler for this event, and no handler in the current state, so ignore it.

return;

}

runTransition(stateInfo, next, { event, data });

}

function runTransition(stateInfo, transition, eventData) {

let targetState = transition.target;

// If we're leaving this state, run the exit action first.

if(stateInfo.exit && targetState) stateInfo.exit(eventData);

// Run the transition action if there is one.

if(transition.action) transition.action(data);

if(!targetState) {

// If the transition has no target, then it's just an action, so return.

updateStore();

return;

}

// Update the state if the transition has a target.

currentState = targetState;

// And then run the next state's entry action, if there is one.

let nextStateInfo = machineConfig.states[currentState];

if(nextStateInfo.entry) nextStateInfo.entry();

updateStore();

}

return {

// Only expose the subscribe method so that outsiders can't modify

// the store directly.

store: {

subscribe: store.subscribe,

},

send: sendEvent,

};

}

Note that both the action and the target on a transition are optional. If we want to just alter a variable and stay in the current state, or even do nothing at all, that’s fine.

Adding Asynchronous Actions 🔗

Asynchronous actions take a little more care. They can succeed or fail, and other events may occur while they are running. We should handle all of these cases. (Again, syntax copied from XState.)

{

on: {

search: { target: 'SEARCHING' },

},

states: {

SEARCHING: {

entry: entryFn, // runs first

invoke: {

src: (context, {event, data}, abortController) => asyncFunction(),

onDone: { target: 'SEARCH_FOUND', action: searchFoundAction },

onError: { target: 'SEARCH_FAILED', action: searchFailedAction },

},

exit: exitFn, // runs last

}

}

}

The action on the SEARCHING state specifies a handler and which transitions to run when the handler succeeds or fails. The onDone transition’s action is called with the handler’s result as its argument, while the onError handler receives whatever error was thrown.

If an event arrives that results in a state transition while the asynchronous action is running, the state machine will attempt to abort the asynchronous action, and it passes the abortController argument to the action handler to facilitiate this. An AbortController’s signal can be provided to a network request or otherwise handled to cancel an ongoing operation.

So let’s implement all this. The only function that needs to change is runTransition.

var currentAbortController;

function runTransition(stateInfo, transition, eventData) {

let targetState = transition.target;

if(targetState) {

// We're transitioning to another state, so try to abort the action if

// it hasn't finished running yet.

if(currentAbortController) currentAbortController.abort();

// Run the exit action

if(stateInfo.exit) stateInfo.exit(context, eventData);

}

// Run the transition's action, if it has one.

if(transition.action) transition.action(eventData);

if(!targetState) {

// If the transition has no target, then it's just an action, so return.

updateStore();

return;

}

// Update the state if the transition has a target

currentState = targetState;

// And then run the next state's entry action, if there is one.

let nextStateInfo = machineConfig.states[currentState];

if(nextStateInfo.entry) nextStateInfo.entry(eventData);

// Run the asynchronous action if there is one.

let asyncAction = nextStateInfo.action;

if(asyncAction) {

// Create a new abort controller and save it.

let abort = currentAbortController = new AbortController();

asyncAction.src(eventData, abort)

.then((result) => {

// If the request aborted, ignore it. This means that another event

// came in and we've already transitioned elsewhere.

if(abort.signal.aborted) { return; }

// Run the success transition

if(asyncAction.onDone) {

runTransition(nextStateInfo, asyncAction.onDone,

{ event: 'invoke.onDone', data: result });

}

})

.catch((e) => {

if(abort.signal.aborted) { return; }

// Run the failure transition

if(asyncAction.onError) {

runTransition(nextStateInfo, asyncAction.onError,

{ event: 'invoke.onError', data: e });

}

});

}

updateStore();

}

One feature of this implementation is that self-transitions are possible. If the user changes the URL and resubmits while a search is running, the state machine code will cancel the currently-running search, exit the SEARCHING state, and reenter it again. This includes running the exit and entry actions, if they exist.

Here’s one last look at the full, updated state machine definition.

{

initial: IDLE,

on: {

'search': { target: SEARCHING }

},

states: {

// We start here

[IDLE]: {},

// Looking for the campaign the user selected

[SEARCHING]: {

invoke: {

src: (ctx, {data}, {signal}) => client.get(

'/api/get-campaign',

{ searchParams: { campaign: url }, signal }

).json(),

onDone: {

target: SEARCH_FOUND,

action: (ctx, {data}) => (ctx.currentCampaign = data)

},

onError: { target: SEARCH_ERROR }

}

},

// Couldn't find the campaign

[SEARCH_ERROR]: {},

// Found the campaign, so we show the campaign details and an "Add" button.

[SEARCH_FOUND]: {

on: {

'submit': SUBMITTING,

},

},

// Adding the campaign to the database

[SUBMITTING]: {

invoke: {

src: (ctx, event, {signal}) => client.post(

'/api/submit-campaign',

{ json: currentCampaign, signal }

).json(),

onDone: { target: SUBMIT_SUCCEEDED },

onError: { target: SUBMIT_ERROR }

},

on: {

// Don't start a search while submitting.

'search': {},

}

},

// It worked!

[SUBMIT_SUCCEEDED]: {},

// It didn't work.

[SUBMIT_ERROR]: {}

}

}

So with all that, our “Add a Cause” page has all of its logic embedded into the state machine, and robustness returns to the code. Anything that needs to be done can be accomplished by sending events to the state machine, and the logic embedded therein will make sure that the right thing happens. We even get cancellable network requests for free!